Beyond Compliance: How Part 108 Unlocks a New Operating Model for State and Local Drone Programs

Let’s start with the good news: state and local agencies have done something remarkable over the past several years. Without a regulatory framework designed for them, without dedicated funding streams, and often without much guidance at all, public sector drone programs have quietly become real. Police departments are running Drone-as-First-Responder programs. Fire agencies are mapping wildfires in real time. Transportation departments are inspecting bridges that would otherwise require lane closures and bucket trucks. Environmental teams are monitoring watersheds and wildlife corridors.

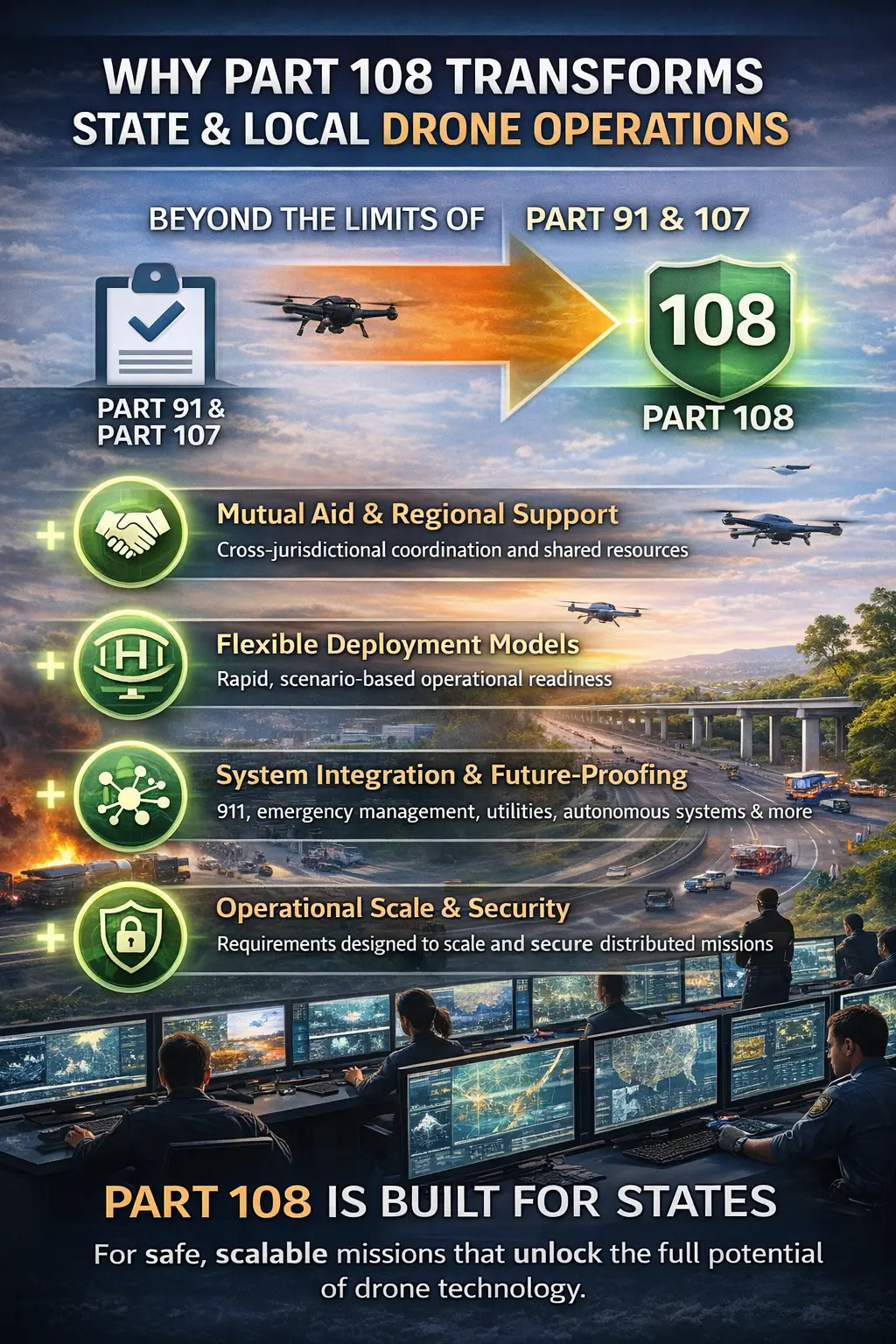

This happened under Part 107, Part 91, and in some cases Part 135—frameworks that were never designed for persistent, cross-jurisdictional, or scalable public-sector operations. And yet, here we are.

But here’s the thing: the frameworks that got us here aren’t the frameworks that will take us where we need to go. Part 108 isn’t just changing the rules. It’s changing the entire operating model. And agencies that engage early will shape how these capabilities are used, shared, and integrated—rather than scrambling to adapt later when the pressure is already on.

Where State and Local Drone Programs Are Today

Take a moment to appreciate how far things have come.

Across the country, agencies are operating under a patchwork of frameworks that each serve a purpose. Part 107 pilots support public safety, infrastructure inspections, environmental monitoring, and emergency response. Part 91 public aircraft operations handle specific government missions with their own set of authorities. A handful of agencies have pursued Part 135 certificates or partnerships for specialized logistics and unique use cases.

These frameworks enabled adoption. They gave agencies a legal pathway to put drones in the air and start building institutional knowledge. That matters enormously—you can’t learn how to operationalize a capability you’re not allowed to use.

But if you’ve been running one of these programs, you already know the constraints. And those constraints get louder as your ambitions grow.

The Practical Limitations of Current Frameworks

This isn’t about legal theory or regulatory critique. It’s about the friction you experience every day when you try to do more with your drone program.

Line-of-sight constraints limit how much ground you can cover and how quickly you can respond. If your operator needs eyes on the aircraft, your coverage area is measured in hundreds of meters—not the miles that actually matter during a search-and-rescue operation or a wildfire.

Mission-by-mission approvals and waivers slow everything down. Every new use case, every new location, every expansion of capability requires paperwork, waiting, and uncertainty. That’s fine when you’re experimenting. It’s exhausting when you’re trying to operationalize.

Crew-centric models don’t scale the way public sector operations need to scale. When everything depends on having a specific certified pilot available, you’re one sick day or shift conflict away from grounding your capability. Try explaining that to an incident commander who needs aerial situational awareness now.

Jurisdictional silos make mutual aid harder than it should be. Your neighboring county has a great drone program. You have a great drone program. But when a disaster crosses the county line, suddenly everyone’s operating under different authorities, different procedures, different training standards. Coordination becomes a negotiation.

And then there’s the gap between certification and readiness. Passing a Part 107 exam proves you understand airspace classifications and weather minimums. It doesn’t prove you can operate effectively at a structure fire with smoke obscuring your view, radio traffic competing for your attention, and an incident commander asking for imagery you’ve never been trained to capture.

These aren’t failures of your program. They’re symptoms of frameworks that were never meant for what you’re trying to do.

What Makes Part 108 Fundamentally Different

Part 108 isn’t Part 107 with extra paperwork. It’s a different philosophy about how drone operations should work.

The most important shift is that BVLOS becomes the baseline, not the exception. Current frameworks treat beyond-visual-line-of-sight operations as something exotic that requires special justification. Part 108 assumes that’s how drones will actually be used—remotely, at scale, over meaningful distances. The framework is built around that reality instead of treating it as a deviation from the norm.

The second shift is from individual approvals to system-based compliance. Instead of proving that each specific mission deserves authorization, you demonstrate that your organization has the systems, training, and processes to conduct operations safely. Once you’ve established that foundation, you can operate within it without returning to the regulator every time your mission profile changes.

This is huge for government agencies. Your missions don’t happen on a schedule. Emergencies don’t submit waiver requests in advance. A framework that recognizes operational readiness—not just pilot certification—is a framework that actually matches how public safety works.

Part 108 also anticipates persistent, distributed operations. Multiple aircraft. Multiple operators. Multiple jurisdictions. Regional coordination. These aren’t edge cases that require creative workarounds—they’re expected operating models that the framework is designed to support.

Why Part 108 Is a Force Multiplier for State and Local Government

Here’s where things get interesting for public sector leaders.

Mutual aid becomes practical instead of theoretical. Right now, sharing drone resources across jurisdictional boundaries is complicated by different operating authorities, different training standards, and different procedures. Under Part 108, agencies operating under the same system-based compliance framework can share aircraft, share crews, and respond to incidents together without the coordination overhead that currently makes mutual aid more trouble than it’s worth. When the next major disaster hits, the conversation shifts from “whose authority are we operating under?” to “where do you need us?”

Deployment models become flexible in ways they aren’t today. Dynamic tasking during emergencies. Persistent monitoring without staffing escalation. Regional or statewide operating centers that can support local agencies without requiring every jurisdiction to build redundant capability. These aren’t science fiction—they’re natural extensions of a framework designed for remote, distributed operations.

Readiness becomes the metric that matters. Part 108’s emphasis on system-based compliance means agencies can train for scenarios, not just checkrides. Crews stay current through simulation and recurrent training that maps to actual mission profiles. Aircraft and systems are validated continuously, not just at certification time. When the call comes, you’re not hoping your people remember what they learned six months ago—you know they’re ready because your system proves it.

Integration with other government systems becomes achievable. Emergency management platforms. Transportation agency operations centers. Utility coordination. 911 dispatch. These connections have always been theoretically possible, but the operational overhead of current frameworks made them impractical for most agencies. Part 108’s emphasis on persistent operations and system-based compliance creates the foundation for drones to become part of your broader operational infrastructure—not a standalone capability that exists in its own silo.

Part 108 isn’t really about drones. It’s about operational coordination. Drones just happen to be the capability that’s forcing the conversation.

A Shift in Mindset: From Regulating Drones to Using Them

This might be the most important section of this entire piece, and it’s the one that’s hardest to say without sounding critical of the work agencies have already done.

For most state and local governments, the drone conversation over the past several years has been dominated by policy questions. How do we write rules for this? How do we manage the risk? How do we limit our exposure? What happens if something goes wrong?

These were the right questions to ask when the technology was new and the regulatory landscape was uncertain. Caution was appropriate. Nobody wanted to be the agency that made headlines for the wrong reasons.

But Part 108 creates space for a different question: How do we operationalize this capability responsibly?

That’s not a question about limiting risk. It’s a question about creating value. It’s a question that assumes drones are going to be part of your operational toolkit—and focuses energy on making them effective rather than making them safe enough to tolerate.

Agencies that engage with Part 108 early will have the opportunity to influence standards, shape best practices, and build internal confidence before external pressure forces the issue. Agencies that wait will find themselves reacting to frameworks they had no hand in creating, adapting to requirements designed without their input, and trying to build capability under exactly the kind of time pressure that leads to mistakes.

The window for shaping this conversation is open now. It won’t stay open forever.

How Virabelo Supports Agencies—Now and Into Part 108

We built Virabelo to be useful regardless of which regulatory framework you’re operating under, because we knew the frameworks were going to evolve and we didn’t want our customers to be stuck with tools designed for yesterday’s rules.

For agencies operating under current frameworks today, we help you track crew qualification and readiness across your program. We prepare operators through simulation-based training that goes beyond regulatory minimums. We manage the operational complexity that comes with running a real program across multiple teams and assets. And we help you build consistency without requiring you to rewrite your policy manuals every time something changes.

For agencies preparing for Part 108, we help you make the mental shift from waiver-based thinking to system-based readiness. We design training around real mission scenarios, not just the knowledge areas that appear on certification exams. We help you build operating models that can scale across regions and support mutual aid from day one. And we provide the documentation and compliance infrastructure that Part 108’s system-based approach will require.

The goal isn’t faster regulatory approval. The goal is confidence at scale—knowing that when the mission comes, your people, your aircraft, and your systems are ready to perform.

A Practical Next Step for State and Local Leaders

You don’t need to abandon your current framework. Everything you’ve built still has value, and Part 107 operations aren’t going away.

You don’t need to predict every regulatory detail. The final Part 108 rule will have surprises, and anyone who tells you they know exactly what it will contain is guessing.

What you do need is to start thinking operationally. Not “how do we stay compliant?” but “how do we build a capability that delivers value when it matters?”

Agencies that engage now will lead. They’ll influence standards. They’ll build relationships with regulators. They’ll develop institutional knowledge that can’t be acquired overnight.

Agencies that wait will adapt under pressure. They’ll implement requirements they didn’t help shape. They’ll train crews on compressed timelines. They’ll learn lessons the hard way that others learned years earlier.

The regulatory change is coming regardless. The only question is whether you’ll be ready for it.

Final Thought

Part 108 isn’t a regulatory event. It’s an operational opportunity.

For state and local governments, the question isn’t whether drones will become more capable. That’s inevitable. The question is whether your organization will be ready to use that capability when it matters most—when the wildfire is spreading, when the search area is expanding, when the incident commander needs eyes in the sky and doesn’t have time to wait for you to figure it out.

If your agency is thinking about how Part 108 could change your operating model—not just your policies—we’d welcome the conversation. This is the stuff we think about constantly, and we’re always happy to compare notes with people who are serious about getting it right.