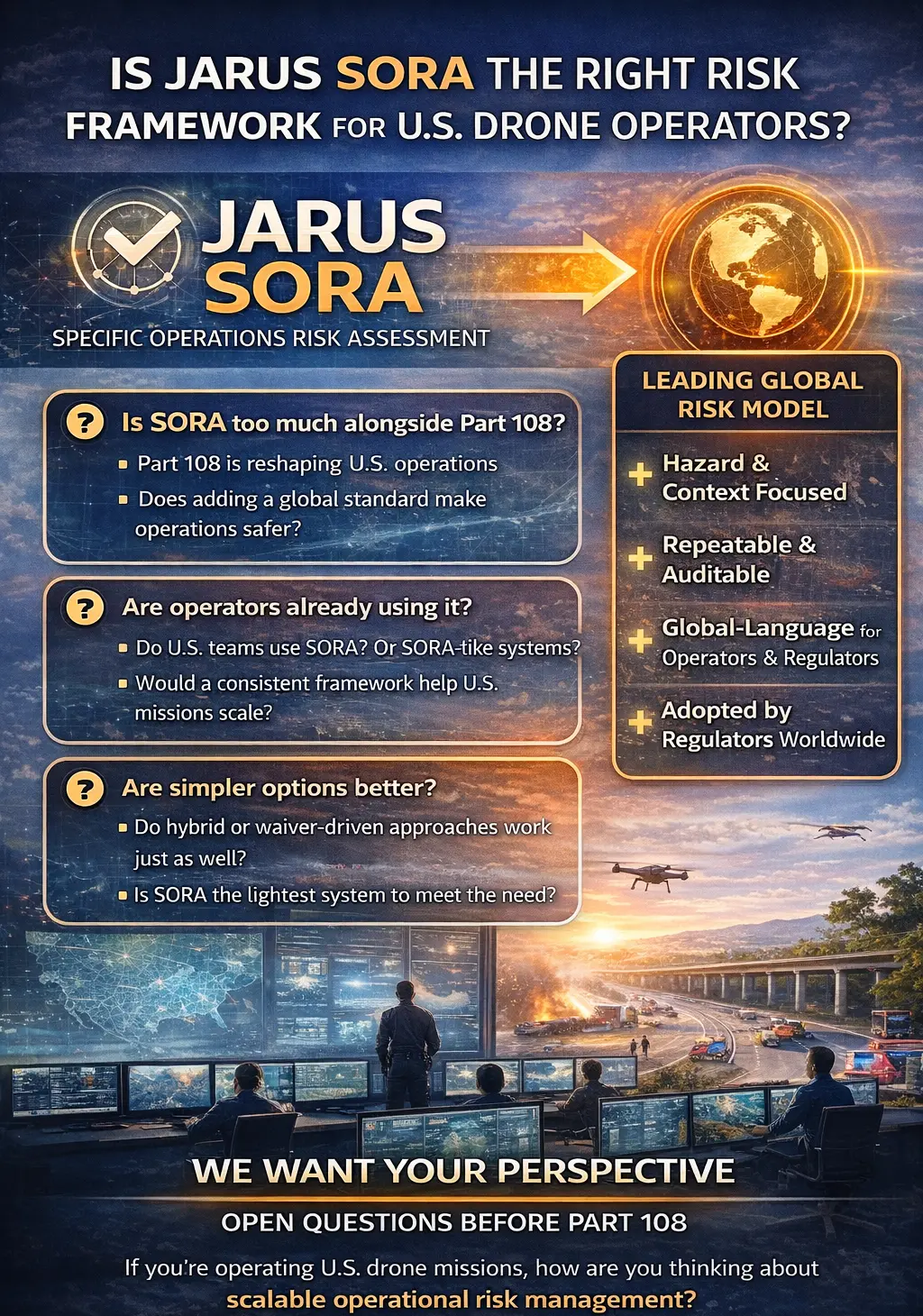

Safe Drone Operations at Scale: Is JARUS SORA the Right Risk Framework for the U.S.?

As commercial drone operations move toward scale—particularly with BVLOS and Part 108 on the horizon—the conversation around safety is shifting in ways that matter.

For years, safety in U.S. drone operations has largely meant compliance. Follow Part 107. Operate under Part 91 public aircraft rules. Adapt crewed-aviation frameworks like Part 135. Check the boxes, file the paperwork, stay out of trouble. These approaches enabled early adoption, and we should give them credit for that. But they weren’t designed to support persistent, distributed, and increasingly autonomous operations. They were designed to manage risk for a world that’s rapidly becoming yesterday’s world.

Globally, a different conversation has been happening—one focused not just on compliance, but on risk management as a system. And at the center of that conversation is something called JARUS SORA.

If you haven’t encountered it yet, you probably will soon. So let’s dig into what it is, why it’s gaining attention, and whether it makes sense for U.S. operators to care about it.

What Is JARUS SORA, Anyway?

The Specific Operations Risk Assessment—SORA for short—is a framework developed by the Joint Authorities for Rulemaking on Unmanned Systems (JARUS). It’s widely regarded as the leading global standard for assessing and managing risk in unmanned aircraft operations, and it takes a fundamentally different approach than traditional regulatory compliance.

Rather than prescribing one-size-fits-all rules that every operator must follow regardless of context, SORA asks a different question: What are the actual risks of this specific operation, and how are you mitigating them?

The framework evaluates both ground risk and air risk. It considers the operational context—where you’re flying, what’s below you, what else is in the airspace—not just the aircraft itself. It links risk levels to specific mitigation strategies. And critically, it encourages operators to build repeatable, auditable safety cases that can evolve as operations change.

Regulators across Europe, Asia-Pacific, and other regions have adopted or referenced SORA as a foundation for scalable UAS operations. It’s become something of a common language for talking about drone safety in a way that transcends specific national regulations.

In short: SORA is less about what rule you’re operating under and more about how safe your operation actually is. That’s a meaningful distinction.

Why SORA Is Gaining Attention Right Now

Several trends are converging that make risk-based frameworks increasingly attractive.

BVLOS is becoming routine rather than exceptional. When every flight required line-of-sight, the risk profile was relatively contained—your operator could see problems developing and react. Once you’re flying beyond visual range, the safety conversation changes fundamentally.

Autonomous and semi-autonomous operations are increasing. When a human is making every decision, you can rely on judgment and training to handle unexpected situations. As automation takes over more functions, you need systematic ways to ensure the system itself is safe, not just the humans supervising it.

Mixed airspace is becoming more complex. Drones sharing space with crewed aircraft, other drones, and eventually urban air mobility vehicles creates interaction risks that didn’t exist when everyone was flying alone in Class G airspace over empty fields.

And perhaps most importantly, public trust is becoming a gating factor for expansion. The industry’s license to operate at scale depends on demonstrating that safety is being taken seriously—not just claimed, but proven.

Traditional regulatory checklists don’t always scale well under these conditions. They tend to be static, binary, and disconnected from operational reality. Risk-based frameworks like SORA are attractive precisely because they adapt to new mission types, scale across geography, and provide a common safety language between operators and regulators.

This is especially relevant as the FAA moves toward Part 108, which emphasizes system-based compliance and operational readiness rather than individual waivers and pilot-centric approvals.

The Big Question for U.S. Operators: Is SORA Actually Necessary?

This is where the conversation gets genuinely interesting—and where reasonable people disagree.

Many U.S. operators we talk to ask variations of the same questions: Isn’t this overkill given Part 107, Part 135, and upcoming Part 108? Will the FAA even care if we use SORA? Aren’t we already doing this implicitly through our waiver applications and safety cases?

These are valid questions, and they deserve honest answers.

In practice, many U.S. operators already perform SORA-like thinking. They identify hazards before missions. They define mitigations for the risks they’ve identified. They document procedures and train crews for specific scenarios. The intellectual work of risk assessment is already happening.

But here’s the thing: it’s often happening in spreadsheets. In PDFs. In one-off waiver packages that get filed and forgotten. Without a consistent, reusable structure that can evolve as operations change and scale.

Every new mission type means starting from scratch. Every new geography means rebuilding the analysis. Every new team member means explaining the reasoning all over again. The thinking is good, but the system for capturing and reusing that thinking is often fragile.

SORA formalizes that thinking and makes it portable. It creates a structure that can be audited, improved, and shared. It turns ad-hoc safety analysis into institutional capability.

Whether that formalization is worth the effort depends on where you are and where you’re going.

How SORA Might Complement Part 108 (Not Replace It)

Let’s be clear about something: SORA is not a replacement for FAA regulations. Part 108 will define what the FAA requires. SORA helps define how operators reason about safety within whatever framework they’re operating under.

They’re not mutually exclusive. In fact, a strong argument can be made that they’re complementary.

Part 108 sets the operating framework—the permits, certificates, training requirements, and compliance obligations that operators must meet. SORA provides a common risk language for thinking through how to meet those requirements safely and systematically.

For operators managing multiple mission types, diverse geographies, shared fleets, or mutual aid relationships with partner organizations, a structured risk methodology may actually reduce friction rather than add it. When everyone is using the same framework to reason about safety, coordination becomes easier. Audits become more predictable. Training becomes more transferable.

The question isn’t whether to follow Part 108 or use SORA. The question is whether SORA-style thinking helps you operate more safely and efficiently within Part 108’s requirements.

Are There Better or Lighter Alternatives?

This is another open question—and one we’re actively exploring rather than claiming to have answered definitively.

Some operators prefer simplified internal risk matrices tailored to their specific operations. Others build company-specific safety cases that address their known mission profiles without the overhead of a comprehensive framework. Still others rely on waiver-driven approaches that have been refined over years of interaction with the FAA.

These approaches can work well, especially for narrow, stable operations. If you’re doing the same mission type in the same geography with the same equipment, you may not need a comprehensive risk framework. You need a good checklist and well-trained people.

The challenge emerges as operations diversify. New aircraft types. New environments. New stakeholders with different risk tolerances. New automation layers that change the human-machine relationship. At that point, informal methods can become brittle. The institutional knowledge that made everything work starts to crack as the people who hold it move on or get stretched too thin.

Whether SORA is the right answer, or whether a hybrid approach makes more sense, likely depends on your scale, complexity, and ambition. There’s no universal right answer here—which is exactly why the conversation matters.

Why We’re Thinking About This at Virabelo

At Virabelo, we’re building an operations and compliance platform designed for the next phase of commercial drone aviation—where scale, safety, and repeatability matter as much as innovation.

We’re actively evaluating how frameworks like JARUS SORA could strengthen what we’re building. Could it improve mission readiness by creating more systematic pre-flight risk assessment? Could it enhance training realism by connecting scenarios to actual risk profiles? Could it support Part 108’s system-based compliance model by providing auditable safety documentation? Could it create a shared safety model that makes coordination between operators and regulators more efficient?

These are genuinely open questions for us. We have hypotheses, but we don’t have all the answers. And we don’t want to design in a vacuum.

We’d Like to Hear From You

If you’re operating in the U.S., we’d genuinely value your perspective on this.

Are you already using SORA or SORA-like frameworks in your operations? If so, what’s working and what isn’t? Do you see value in adopting a global risk standard alongside Part 108, or does it feel like unnecessary complexity layered on top of an already demanding regulatory environment?

Does this kind of structured risk thinking feel like necessary rigor for where the industry is heading? Or does it feel like overhead that gets in the way of actually flying missions?

Are there alternative frameworks you trust more? Internal methodologies that have served you well? We’re genuinely curious what’s working in the field.

The goal here isn’t to import regulation for its own sake. It’s to enable safer operations at scale—and to figure out which tools actually help accomplish that.

Final Thought

The safety conversation in commercial drone operations is evolving. Compliance got us here, but risk management will take us where we’re going.

Whether JARUS SORA is the right framework for U.S. operators—or whether something else emerges as the standard—remains an open question. What’s clear is that operators who develop systematic, repeatable approaches to safety will be better positioned as the industry scales.

If you’re thinking about how safety frameworks will evolve alongside Part 108, we’d welcome the conversation. This is exactly the kind of question we’re wrestling with, and we suspect we’re not alone.